Historical Invention Redux

- cplesley

- Jul 28, 2023

- 3 min read

Updated: Sep 5, 2023

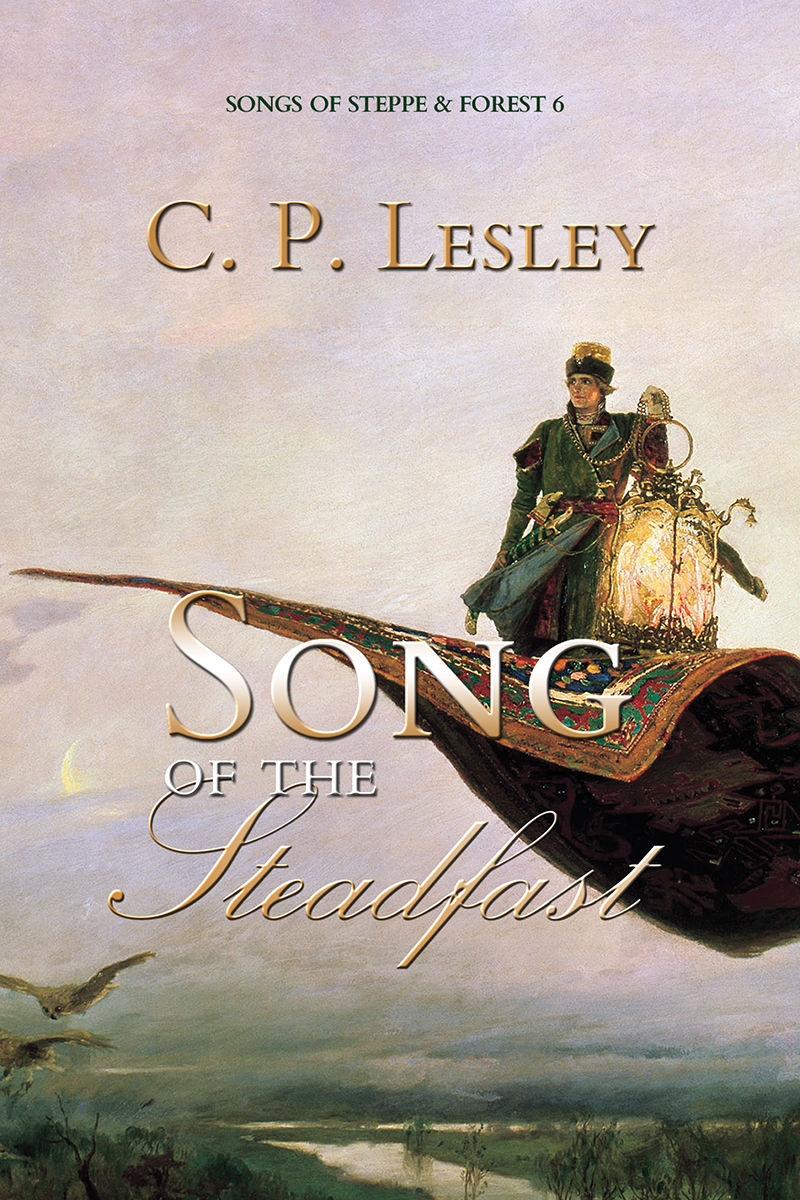

About a month ago, I wrote a post on historical invention, or why some stuff is too wild for a novelist to make up. At the end, I promised to reveal a specific instance affecting the next book in my Songs of Steppe & Forest series, Song of the Steadfast.

As I mentioned there, the novel draws, among other events, on the Great Fire of Moscow (1547) and features two characters—Yuri Vorontsov and Anna Kolycheva—who became betrothed two books ago and later eloped. Why they did those things I prefer not to reveal. If you’d like to know, you can find out from Song of the Sinner and Song of the Storyteller, respectively. The coincidence comes from the intersection of two blindingly specific sources and complete happenstance in the form of Yuri’s last name.

Now, as I mentioned in a long-ago post, finding unique names for characters in not one but two connected series is a challenge. Even today, a lot of Russians have the same first names and can be distinguished primarily by the combination of those first names with their patronymics and surnames. In the sixteenth century, the situation was much worse. Although in principle, newborns were named after saints commemorated on dates close to the birth, that cannot have always been true in practice. The royal family, to cite the most egregious example, had Ivans, Vasilys, Dmitrys, Fyodors, and Yuris in almost every generation, with the occasional Semyon, Boris, or Andrei when the number of sons exceeded five. Other families branched out into Mikhails and Glebs and Daniils, but even there the variation was not great enough to indicate pure chance.

Surnames were even more complex, because in the 1530s and 1540s, when my books are set, the number of clans with the right to ascend to the highest rank of boiarin (boyar) was very small—no more than forty. In addition, there were a large number of princes with last names indicating the place where their ancestors once ruled (some of them now relatively unknown, like Shuia or Kurba), yielding designations that to a Western ear sound almost interchangeable. Last but not least, only noble families actually had surnames in this period, and except for the princes, those changed with every generation. We won’t even get into nicknames, which then as now vary from one moment to the next.

So, in my novels I have tried since the beginning to simplify the situation by giving each person a unique first name where possible (16th-century Russians had the annoying—for modern novelists—habit of changing their names to signify certain important life transitions) and repeating clan designations across generations and among characters who are somehow related. Hence the choice of Vorontsov for Yuri: it is a well-known aristocratic name going back centuries; I had already used it for Katya, a neighbor of Anna and her family; and existing relationships made him a likely choice for Anna’s potential husband.

That was the first coincidence, as it turns out, although I didn’t recognize that at the time. The second was my decision to include the Great Fire of Moscow in Yuri and Anna’s novel for dramatic effect. The third was an article that crossed my path in the course of my day job, which included a map showing exactly which regions of the city burned. (This is important because street names have changed and the churches that people in the 1530s used as landmarks were in most cases destroyed by the Bolsheviks.) This map made it possible for me to trace the location of the fires in the guidebook to contemporary Moscow that sits on my desk.

And that’s where I ran into the part no one could make up: for whatever reason, the account from the chronicle I most often use explicitly describes what happened to the Vorontsovs’ house in the city and the gardens and orchards that the family owned outside the city walls. Why they were singled out for mention, I have no idea. Perhaps someone associated with them recorded the entry. What I do know, thanks to the sources mentioned above and the magic of Google Maps, is exactly where that estate stood and how long it took to travel by foot from what were then the outer walls of Moscow to what even today is known as “Vorontsov Field.”

I won’t say more than that, because it would give away spoilers. But when you read it in print a year or so from now, you will know that—even though the characters and everything they say and do are fictional, the setting is real. And that’s what I mean when I say that the weirdest stuff is the things you don’t have to invent.

Comments