Adjusting to Co-Writing

- cplesley

- Dec 8, 2023

- 3 min read

I am, I freely admit, a control freak. Not the kind who keeps everyone else in line—at least I hope not, although my family may disagree—but the kind who plans well into the future, despite knowing that life has a tendency to toss a spanner in the works. This personality trait of mine is reflected in my job: although I trained as a historian, I have spent much of my career line editing (edits that focus on every comma and double space) and ensuring that the trains of my particular gig run on time. Even my exercise of choice—classical ballet, the least forgiving of disciplines, in which every fingertip has its place—speaks to my love of detail. But co-writing has tested that tendency in a whole new way.

That’s because the one exception to my “you can’t overplan” rule is writing fiction. For me, jotting down stories is an arena where I blissfully ignore outlines and inconsistencies, at least until I reach the end of the first draft. The one time I tried to take part in National Novel Writing Month (known affectionately as NaNo and set to take place every November), the process nearly drove me insane. Mini-deadlines every day, thirty word count targets, one big goal at the end—I couldn’t stand all that structure. That’s what work is for; fiction is for tossing a ball of imaginary yarn in the air and letting the characters run where they will as they try to catch it.

That’s all very well when everything depends on me and my unstructured imagination. It also explains why my early attempts at writing historical mysteries didn’t work out: you need more than a vague sense of where a tale is heading to strew clues along the path. But when I paired up with the ultra-disciplined and productive P.K. Adams—who does write mysteries, and very good ones at that—to produce The Merchant’s Tale, it was clear something would have to change.

True, we both knew that characters don’t always cooperate with an author’s plans for them and good ideas sometimes appear on the fly, but if one person is taking charge of chapters 1, 3, and 5 while the other focuses on 2, 4, and 6, you both have to be able to trust that the story won’t go sideways in chapter 3, sending 4 and 6 down another path altogether. And if you think I’m exaggerating, I’m not. Back in 2012 or thereabouts, I drew up a detailed outline for The Winged Horse, which took me at least a month, only to have the story veer off within five pages and head in a completely different direction. After that, I gave up on detailed outlining altogether—for my own projects, at least.

But for this book we needed character studies and précis of historical details and a clear sense of where the book would end and how it would get there, with online discussions if one of us decided something should change. Over the course of writing, we did move the characters around a bit, changed their names a couple of times, and definitely beefed up some plot threads and minimized others. Once in a while, one of us remembered or discovered a detail that threw a cherished element out the door (we had a lovely New Year’s party planned before recalling that most of sixteenth-century Europe didn’t celebrate New Year’s Day on January 1, for example). But that outline, in the form of an Excel spreadsheet, remained more or less solid from beginning to end.

What did I learn from the experience? Well, lots of things about respecting someone else’s space and accepting different takes on the same problem and finding solutions to disagreements about how a particular character should develop. Co-writing is like any other partnership, after all: it requires a willingness to listen and to learn, as well as the ability to express one’s own views respectfully and negotiate compromises. I’ll even agree that for a co-written project, sticking to an outline is essential.

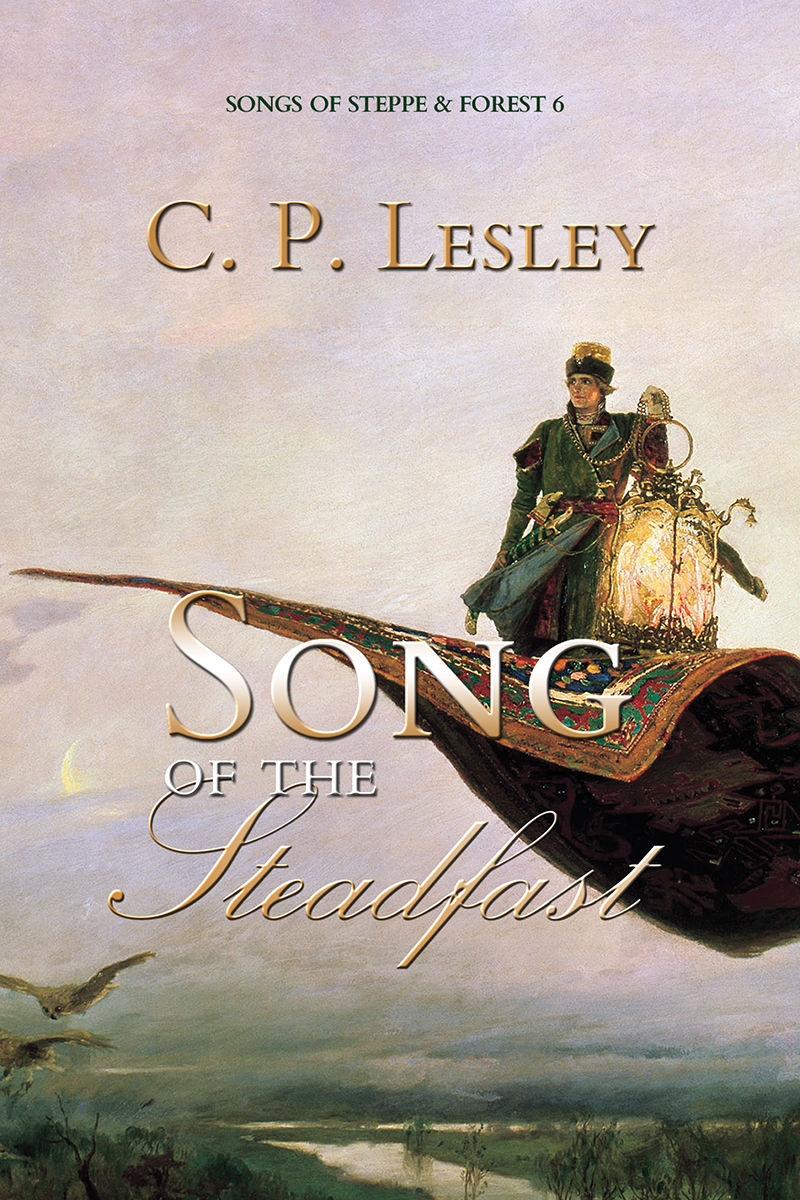

But I’ve also come to realize that what I love most about fiction is the moments of inspiration—like the sudden appearance of Mina the Cat in Song of the Steadfast (my current project) or Lyuba’s ride in the meadow with Timur and their falcons in Song of the Storyteller. Those elements weren’t in my mind when I started to write, but they flowed onto the page and they worked for the characters. So even though it’s true that a more detailed outline might have stopped me from being stuck for the last four months, in part because I hadn’t carefully worked out the progression of the Great Moscow Fire of 1547, I doubt that I’ll be crafting an outline for my own novels anytime soon.

Comments